Beyond the Gates: A Cemetery Explorer’s Guide to Rumney Marsh Burial Ground Revere, MA

Beyond the Gates: A Cemetery Explorer’s Guide is a blog hosted by The Friends of Mount Auburn Cemetery written and researched by Corinne Elicone and Zoë G. Burnett. Our intention for this blog is to rediscover the out of the way and obscure graveyards that surround us, as well as to uncover new histories among the more well-trod grounds of prominent burial places. With this blog as a guide, visitors can experience cemeteries in a new way. As important landmarks of cultural heritage, our hope is that interest in these quiet places will help to preserve and educate us about our past and, ultimately, everyone’s shared future.

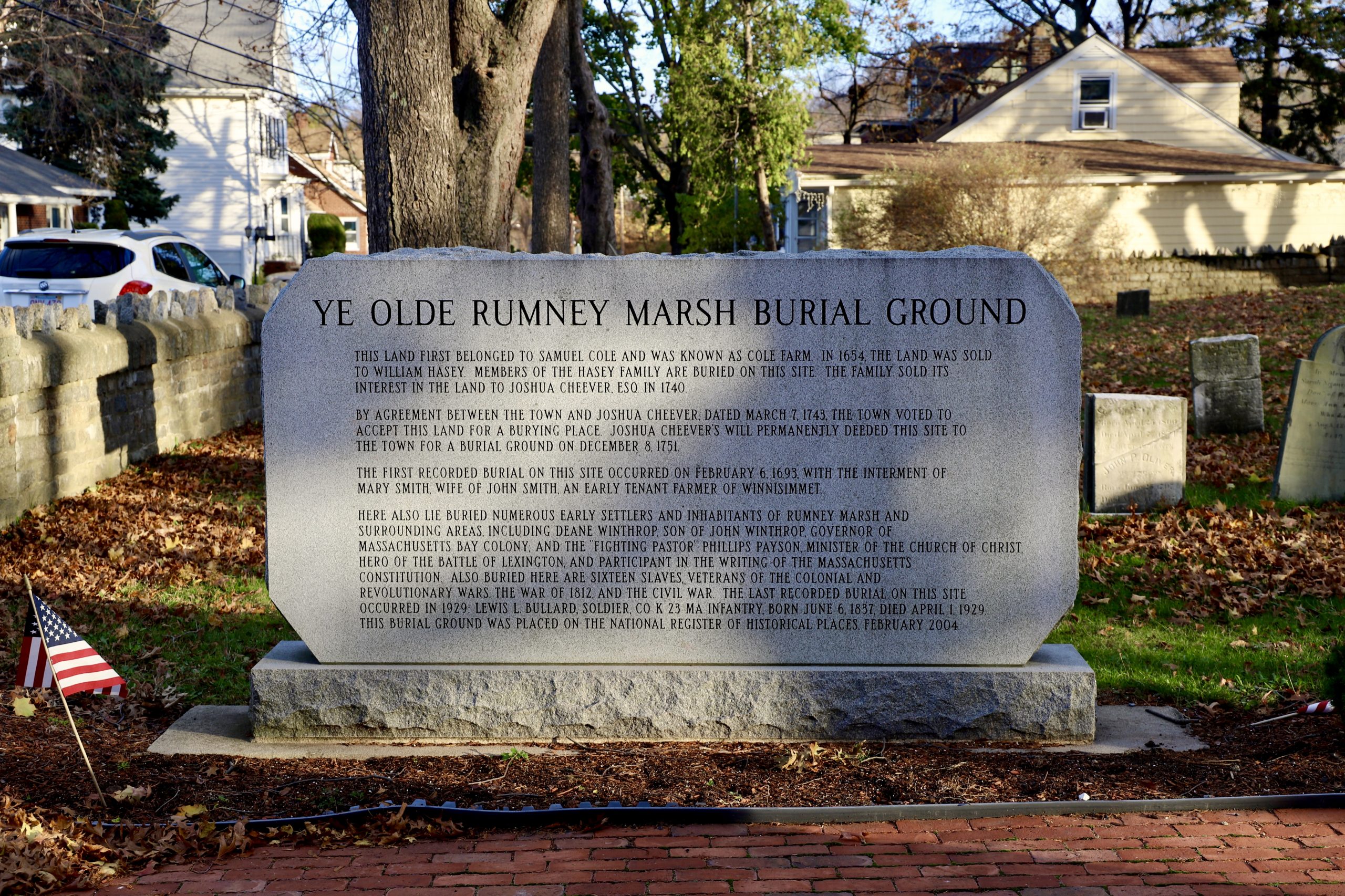

RUMNEY MARSH BURIAL GROUND | REVERE, MA (1693)

Revere Massachusetts, often overlooked by the metropolis of Boston, has a removed nostalgic flavor for me – An area important to my upbringing, that I seldom visited. My grandmother grew up working class in Everett (the town that borders Revere) in the 50’s with her Swedish mother– both of them tough as nails through and through. When my grandmother married and had kids of her own, and then her kids had kids, well, that’s where I come into the picture. Far removed from her stories of the suburbs (if you can call it that) of East Boston, but captivated by her descriptions of 50’s highschool fashion, the corner stores, the rivalry between Somerville, and (most disappointingly) the sewing kit neatly hidden in a tin of Danish cookies –regrettably a phenomenon that appears to be universal across generations. One of the only times in my memory that I can recall actually laying my eyes on these locations of legend, I was driving through Everett and Revere with her soon after my grandfather died. I was 19. She pointed out everything as we drove by, “there’s the dry-cleaning place my mother used to send me”, “I met your grandfather on that beach” pointing to Revere Beach dotted with sandcastles. We were on our way to Woodlawn Cemetery in Everett to purchase a plot for my grandfather who passed away suddenly just days before. I could tell it was emotional for her driving through these old neighborhoods–so much of it exactly how she left it, but a lifetime and a life-ended in between.

I mention this story because upon arriving at the Rumney Marsh Burial Ground it is immediately clear to me that this cemetery has been and continues to be the object of genuine care and affection from the Revere community. Between the friendly abutters waving at me as I trudge through the burial ground with my camera and the newly installed memorial bench, plaque, and entry sign, – a glimpse of the community that I had been so far removed from comes into clearer focus.

I introduce myself to Brendan O’Brien, in that kind of awkward way that the pandemic has everyone enduring: standing 10 feet away, muffled by a KN95 mask, and noticeably lacking in a handshake and a visible smile. O’Brien got in touch with me via email after being a reader of this blog series, generously hoping to share this little colonial burial ground with me. As I understand it, O’Brien is part of a larger group of stewards of this place called The Rumney Marsh Burial Ground Renovation Committee. With a background in preservation and a flair for history O’Brien begins his tour, something it’s very clear he missed hosting during the pandemic.

Rumney Marsh’s first recorded burial was in 1693. William Hasey, not the recipient of the first burial, but owner of the oldest remaining gravestone, also owned the land at the time of Rumney Marsh’s founding as a burial ground. The Hasey family became concerned for their legacy when a smallpox outbreak in the 1690’s prohibited the return of infected corpses to Boston for burial. Anyone discovered in a plot to sneak a body into Boston would be fined 5 pounds. In response to this new policy, the Hasey’s set aside some of their land for a new burial ground that became Rumney Marsh officially in the 1740s. Boasting notable figures from Revere, East Boston, Chelsea, and Winthrop (amongst others) Rumney Marsh is the connection point of the community’s earliest settlers, up until its last burial in 1929.

“Why did the burial ground close in the 20s? Was it full?” I asked O’Brien, who was quick to point out that burial tastes had changed-even long before the 20th century. With the creation of Woodlawn in Everett and even Mount Auburn in Cambridge these colonial burial grounds had gone out of style. “Even in the late 1800’s burials here were rare.” He said. O’Brien tells me that he came across a hidden gem when researching the burials here. The Rosetta Stone of Rumney Marsh (if you will) is an 1897 map of the grounds (currently rolled up in a closet of a Boston archive) with inexplicable specificity on who is buried where in the cemetery–marked or unmarked. O’Brien and the committee have sought to digitize this map for quite some time, but have had trouble getting their hands on it. “Based on the 1897 map” he says, “it doesn’t appear as though Rumney Marsh is completely full”. Also a rarity when it comes to burial grounds this old, Rumney Marsh doesn’t appear to have been rearranged over the years.

Along the north wall by the entrance to the burial ground are two recently installed plaques to commemorate the enslaved and free men, women, and children who are buried in unmarked graves beneath. “Never forget that they were human beings who contributed to our community’s history”, the plaque reads.

According to research done by the committee, a 1938 book called “The History of Revere” by Benjamin Shurtleff indicated that three Black individuals, two free: Job and Betty Worrow and one enslaved: Fanny Fairweather are actually buried in the south-east corner of the burial ground, and not with the others by the entrance to the cemetery.

Shurtleff’s book alludes to the fact that Fairweather’s monument is long gone at the time of the writing his book. Shurtleff goes even further to say that the inscription on Fairweather’s monument read “ Fanny Fairweather, died 1845, age 80, a native of Africa.” How Shurtleff would have any idea what is inscribed on a disappeared stone is still in question.

Of all the Black individuals buried at Rumney Marsh, the most information exists on Job Worrow, a veteran of the Revolutionary War. Worrow served under Captain Samuel Sprague (also buried at Rumney Marsh) at Pullen Point in Winthrop. Early in his life Worrow lived on Deer Island, later he would move to Shirley with his wife, Anna Sennie who was half Black and half Indigenous. It is recorded that he died in a poorhouse in Chelsea at 100 years old.

ICONOGRAPHY

At Rumney Marsh there are many great examples of work by the early New England stone carvers such as Robert Fowle and Richard Adams, but what stood out to me most of all was the charming little imps accompanying many a winged skull on numerous stones. Too small to catch from afar, I hadn’t even noticed them until O’Brien pointed them out to me: rotund and surreptitiously holding banners sculpted in stone.

Little precious details appear to be the reward of curious cemetery sleuths meandering the grounds at Rumney Marsh: tiny skulls, little imps, mysterious circles, a broken stem of a flower, it left me wondering what else I hadn’t captured on my short 40 minute stint there.

The most in-your-face monument I encountered was a rather striking stone with an individual portrayed as a portrait bust sculpture, smiling innocently. Unbeknownst to the smiling subject of art-within-art… there is a skeleton aiming directly at their head with a massive arrow. I mean, the questions I have are endless. Are we team skeleton? Why is it flashing me that Mona Lisa smile? Is this really a meta-commentary on the clash between colonial and neoclassical art? Probably.

PRESERVATION

Just like most New England colonial burial grounds, Rumney Marsh struggles against the tides of time and the disintegration of its precious gravestones. Trees and their roots make worthy adversaries as preservationists wrestle the stones out of tree trunks in an attempt to save them from a certain, woody demise.

Additionally, cordoned off by the entrance to the burial ground are fragments of stones found by O’Brien and other volunteers awaiting preservation. O’Brien told me that he found three fragments of the same stone scattered across the entire cemetery–how one broken stone was able to cover that amount of ground is a mystery to us both.

A big thank you to Brendan O’Brien and the whole Rumney Marsh Burial Ground Renovation Committee for inviting me to cherish this plot of land. I hope to stop by often when visiting my grandfather at Woodlawn Cemetery.

Make sure to check out the RMBGRC’s website for more information on notable burials and other topics here: http://rmbgrc.org/ and follow their amazing work on instagram: https://www.instagram.com/rumney_marsh_burial_ground/

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Corinne Elicone is the Events & Outreach Coordinator at Mount Auburn Cemetery. She curates Mount Auburn’s “death positive” programming, online video content, and historic walking tours of the grounds. She is also Mount Auburn’s first female crematory operator in their near 190 year history.

If you are a representative of a cemetery or a cemetery historian and would like to see your cemetery featured in this blog please email Corinne Elicone at celicone@mountauburn.org

Leave a Reply