David Haggerston, Mount Auburn’s First Gardener and Superintendent

In March 1833, a year and a half after the consecration of Mount Auburn, David Haggerston (1802 – 1863) assumed the duties of the Cemetery’s first gardener and superintendent. Haggerston was described as “one of the most skillful and practical gardeners of the old school” who had “done as much if not more, to develop a taste for plants and fruits in our vicinity than any other gardener of his time.”[i] The British horticulturalist emigrated to the United States from England in 1823 in his early twenties. Before coming to Mount Auburn, he worked as a gardener on the estate of Governor Gore in Waltham and then ran the Charlestown Vineyard in Boston, a successful vineyard and nursery. He became known for his articles about horticulture in publications such as American Gardener Magazine and received particular acclaim for his botanical work to combat invasive insects and disease.

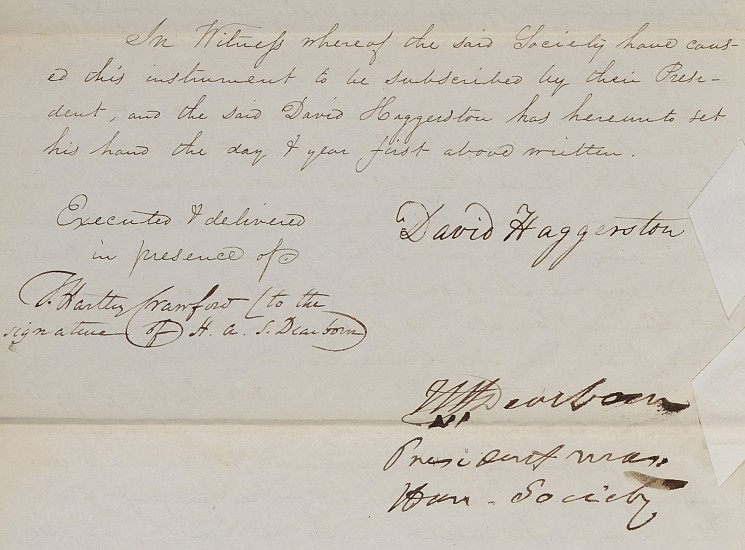

Haggerston was one of the founders of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, established in 1829. The Society organized a Garden and Cemetery Committee to research the idea of creating a cemetery outside of the city of Boston. On June 11, 1831, the Society agreed to purchase 72 acres of wooded land bordering on Cambridge and Watertown for the new burial site that would become a garden and ornamental cemetery. President of the Society and one of the Committee members was Henry A. S. Dearborn who played a significant role in the founding and early design of Mount Auburn. The growing demands for running Mount Auburn, however, necessitated further assistance. [ii] “The need for someone to oversee construction, lay out lots, … and take on the increasing demands for burials, record keeping, and overseeing individual monument building forced the Garden and Cemetery Committee to hire a full-time superintendent,” Blanche M.G. Linden noted in Silent City on a Hill.[iii]

The work of the new superintendent included reporting to the president and board of trustees; supervising staff and contractors on the work of the erection of buildings and fences and laying out of avenues, paths, and lots; overseeing the work of the sexton; and keeping a record of burials. Mount Auburn paid Haggerston a salary of $600 a year and erected a cottage for his residence with his wife, Mary Ann Farwell, with whom he had five children.

The Egyptian Revival Gateway, at the entrance to the Cemetery, provided loges (offices) for the superintendent and a porter (or gatekeeper).[iv] Michael Shahan, who served as gatekeeper from 1833 to 1839, guarded the entrance, checked visitors passes, and ensured regulations regarding visitation to the Cemetery were followed. A talented gardener, Shahan assisted Haggerston in the cultivation of the grounds. The New England Farmer reported that “Mr. H. is assisted in the discharge of his arduous but most interesting duties by the porter, who has special charge of the beautiful and appropriate gateway, at which commences the avenues and paths that lead in every direction on the grounds.”[v]

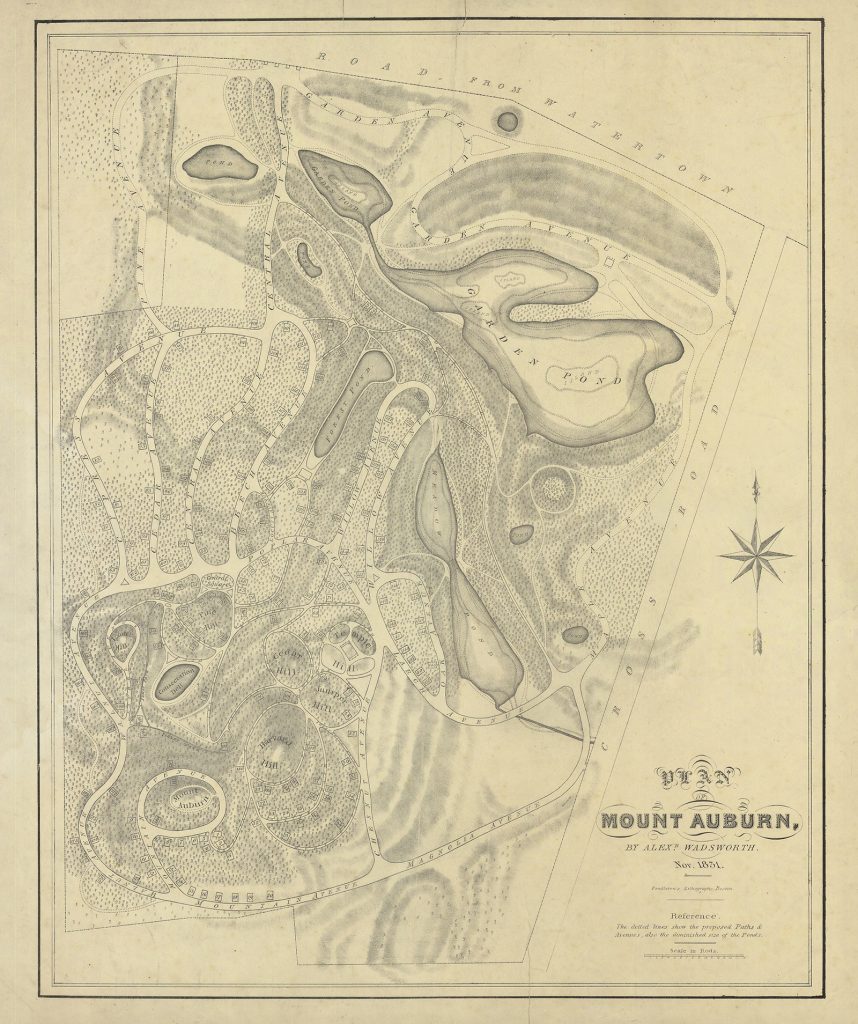

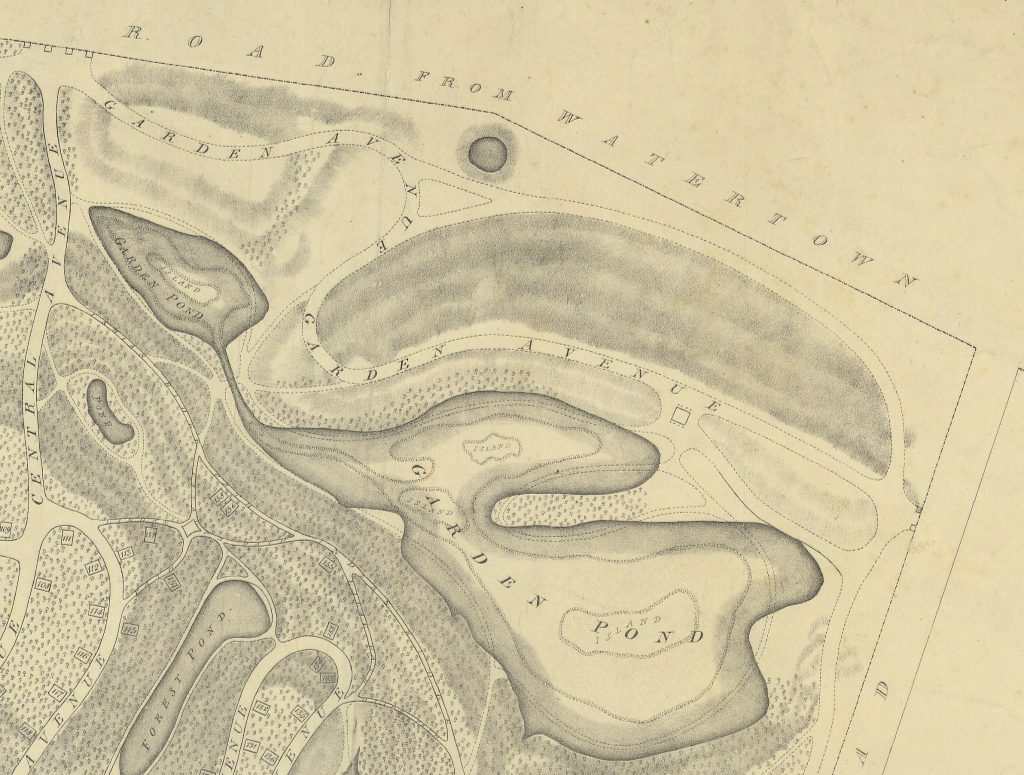

The original concept for Mount Auburn included an experimental garden, of which Haggerston was also appointed gardener. The garden would provide the opportunity for the Society, which was founded to promote the art and science of horticulture, to cultivate and exchange domestic and foreign varieties of fruits, flowers, vegetables, and plants and to conduct horticultural experiments. The garden occupied 32 acres of land in the northeastern section of the Cemetery near the largest of the ponds, Garden Pond, known today as Halcyon Lake. During this period as botany was emerging as a professional discipline, the Society often received gifts of seeds from horticulturalists, botanists, and gardeners around the world. Usually distributed among its members, many of these gifts were now entrusted to Haggerston for use in Mount Auburn’s experimental garden. As Cemetery gardener, Haggerston was responsible for keeping a record of all seeds, plants, and trees he received, their species, and from whom and where they came. Haggerston in turn presented vegetables, fruits, and flowers from the garden for exhibition at the Horticultural Society. For a number of years, Haggerston served as Chairman of the Flower Committee of the Society and helped to arrange and judge many of its exhibitions.[vi]

“I am happy to announce to the Society,” Dearborn reported, “that the plan of the experimental garden at Mount Auburn is in progress, and will soon be carried completely to effect. Mr. Haggerston, the gardener, moved into the cottage early last month, and with two laborers, has been constantly and industriously employed in setting out over one thousand and three hundred forest, ornamental, and fruit trees, planting culinary vegetables, and preparing hotbeds for receiving a great variety of useful plants, which are intended to be distributed over the various compartments of the garden, and on the borders of the avenues and paths. Among the seeds planted are four hundred and fifty varieties which have been sent to the society from Europe, Asia, and South America.”[vii]

The newly appointed superintendent was praised for “his good taste and skill . . . in carrying out the plans of Gen. Dearborn, in laying out the many avenues and various paths which wind with such easy ascent up and around the elevated parts of the grounds.”[viii] Haggerston also oversaw the considerable work of attending to burials and maintaining Cemetery records. By September 1833, Mount Auburn covered 110 acres with 400 hundred burial lots. That year there were 93 interments, 18 tombs built, 15 monuments erected, and 68 lots turfed and planted, some surrounded by iron fences.[ix]

The Boston Herald remembered Haggerston for his “skillful and efficient management” and for “his practical science and taste for which Mount Auburn is so much indebted.”[x] In 1834, he left Mount Auburn to manage the extensive gardens at the estate of Col. John Perkins Cushing in Belmont. He later became superintendent at Mount Hope Cemetery in Boston, where he was buried in 1863. His gravestone notes that he was “First superintendent at Mount Auburn Cemetery” and “Superintendent of Mount Hope Cemetery.” The inscription reads, “The order and beauty here developed by his genius, and the honor and friendship he won by his integrity, are more noble and enduring than a monument of marble.” While Haggerston held the position of superintendent and gardener of Mount Auburn for only one year, he set an exemplary example for superintendents who followed.

[i] “Obituary, Death of David Haggerston,” Magazine of Horticulture, Botany, and All Useful Discoveries and Improvements in Rural Affairs, vol. 1863. [ii] John B. Russell quoted in Robert Manning, History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878 (Boston: Rand, Avery, for the Society, 1880), pp. 89-91. [iii] Blanche Linden, Silent City on a Hill: Picturesque Landscapes of Memory and Boston’s Mount Auburn Cemetery (Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press in association with Library of American Landscape History, 2007), p. 159. [iv] In 1842, Mount Auburn replaced the gateway, which was originally made of wood, with a granite structure. [v] Entry from Medical Journal in the New England Farmer, 1833, vol. 11, p. 395. [vi] “Obituary, Death of David Haggerston.” [vii] Henry A. S. Dearborn in History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878, p. 98. [viii] “Obituary, Death of David Haggerston.” [ix] See History of the Massachusetts Horticultural Society, 1829-1878, pp.103, 107. [x] Boston Herald, June 25, 1852.

Leave a Reply