Mount Auburn, the Rural Cemetery Movement, and Frederick Law Olmsted

Landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted (1822 – 1903) was nine years old when Mount Auburn was founded in 1831. While he did not design the Cemetery, the enduring characteristics that made Mount Auburn a model for cemeteries and public parks would come to deeply influence his work.

Decades before Olmsted took on his first landscape commission, Mount Auburn’s founders were envisioning a green space for the citizens of Boston. Grappling with the problem of overcrowded and sometimes neglected burial grounds and need for more burial space, they wanted to create a new cemetery where the bereaved could come to commemorate loved ones in a designed landscape outside of the city. The founders included Jacob Bigelow (1787-1879), a physician and botanist, and Henry A. S. Dearborn (1783-1851), a politician and horticulturalist, who represented an earlier generation of pre-professional landscape designers.

For the new cemetery, they chose a beautiful, wooded area bordering on Cambridge and Watertown along the Charles River. They found inspiration from English gardens that incorporated naturalistic design principles and from Père LaChaise, the garden cemetery in Paris founded in 1804. Within a few years, Bigelow, Dearborn, and their colleagues created a picturesque landscape where visitors could stroll among Mount Auburn’s gently curving avenues and pathways, exploring memorials thoughtfully placed among the hills, dales, trees, plants, and ponds.

When Mount Auburn opened, people came to visit the gravesites and to seek refuge from urban life. By 1848, the Cemetery welcomed 60,000 visitors annually. Mount Auburn is considered the country’s first rural cemetery―a cemetery with permanent burials, in a landscaped setting outside of the city. By 1865, there were more than 70 rural cemeteries throughout the United States including Laurel Hill in Philadelphia, Green Mount in Baltimore, Green-Wood in Brooklyn, Spring Grove in Cincinnati, and Forest Lawn in Buffalo. Their rapid rise and immense popularity, what came to be known as the “rural cemetery movement,” made evident the need for public green spaces in the country’s growing metropolises. Andrew Jackson Downing, editor of the Horticulturist, observed, “in the absence of public gardens, rural cemeteries in a certain degree supplied their place. But does not this general interest, manifested in these cemeteries, prove that public gardens established in a liberal and suitable manner near our large cities would be equally successful?”[1]

Downing made an appeal for the creation of a public park in New York City. The eventual site, Central Park, would be designed by Frederick Law Olmsted and Calvert Vaux in 1857. Olmsted thus embarked on his first landscape project at a pivotal moment with the rural cemetery movement well underway and the public parks movement beginning. Park and Cemetery, the title of an early professional journal in landscape architecture, reflected the intrinsic link between the two public spaces and common issues relating to design, horticulture, and maintenance of public grounds.

Olmsted referred to himself as a landscape architect as landscape gardening was evolving into the profession of landscape architecture. After Central Park, Olmsted designed Mountain View Cemetery in Oakland, California. He went on to create public parks across the country including those in Brooklyn, Boston, Rochester, Buffalo, Chicago, and Louisville. He often connected his parks through a system of interconnected parkways that created extended green spaces throughout the city.

Central Park, Olmsted explained, represented “a democratic development of the highest significance.”[2] Olmsted intended these “people’s parks” to promote a sense of community, well-being, and health, where people from all walks of life could enjoy the healing benefits of a rural setting within an urban green space. He wrote of “the freedom and repose which must in itself be refreshing and tranquilizing to the visitor coming from the confinement and bustle of crowded streets.”[3]

Sentiments relating to the uplifting power of an urban green space accessible to all had been expressed earlier by Joseph Story, Mount Auburn’s first president. “A rural Cemetery seems to combine in itself all the advantages, which can be proposed to gratify human feelings, or tranquilize human fears,” Story wrote in his consecration address to Mount Auburn in 1831. “There is, therefore, within our reach, every variety of natural and artificial scenery, which is fitted to awaken emotions of the highest and most affecting order.”[4]

Olmsted moved his firm to Brookline, Massachusetts in 1883, and worked on the design of Boston’s chain of parks, parkways, and waterways known as the Emerald Necklace from 1878 to 1896. Suffering from dementia, he spent his last years as a resident of McLean Hospital in Belmont, Massachusetts. McLean was situated on the pastoral site where Olmsted had earlier recommended the institution be built and which was located not far from Mount Auburn. It seems fitting when Olmsted died in 1903, that he was cremated at Mount Auburn, the birthplace of the rural cemetery movement. His cremated remains were eventually deposited in the family vault in the Old North Cemetery in the city of Hartford, Connecticut, where Olmsted was born. After his death, the firm, now known as the Olmsted Brothers (headed by Olmsted’s son, Frederick Law Olmsted Jr., and his nephew and stepson, John C. Olmsted) designed several lots in Mount Auburn.

Olmsted’s encompassing legacy has often led to the misconception that he designed Mount Auburn. Praise of Olmsted, historian Blanche M. G. Linden contends, has sometimes come “at the expense of due recognition of the many pre-professional and early professional landscape designers who contributed to the ‘rural’ cemetery movement.”[5] Understanding the far-reaching influence of Mount Auburn and subsequent rural cemetery movement reminds us of the seminal contributions of Bigelow, Dearborn, Story, and other founders of Mount Auburn. The vision of these individuals, less known and born a generation earlier than Olmsted, helped shape how successive generations would experience the restorative effects of nature and public green spaces in the nation’s metropolises.

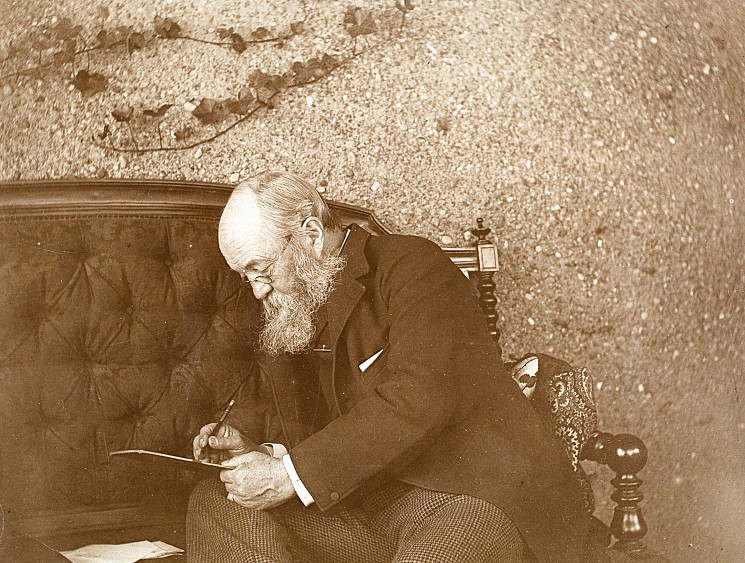

Lead image above: Three-quarter portrait of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., seated on a couch, facing left, in the conservatory at Fairsted, Brookline, Massachusetts, 1895. Courtesy of Hisotric New England.

[1] Andrew Jackson Downing, “Public Cemeteries and Public Gardens,” July 1849 in Landscape Gardening, 10th Edition (New York: John Wiley and Sons, 1921), 374.

[2] Frederick Law Olmsted to Parke Godwin, August 1, 1858, reprinted in The Papers of Frederick Law Olmsted, ed. Charles Beveridge and David Schuyler, Volume 3, (Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1977), 201.

[3] Frederick Law Olmsted and Vaux, Preliminary Report for Laying Out a Park in Brooklyn, 1866 in Olmsted, Frederick Law, et al. Landscape into Cityscape: Frederick Law Olmsted’s Plans for a Greater New York City (Cornell University Press), 1968.

[4] Joseph Story, An Address Delivered on the Dedication of the Cemetery at Mount Auburn, September 24, 1831 in Jacob Bigelow, History of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn (Boston and Cambridge: James Munroe and Company, 1860), 160, 162.

[5] Blanche Linden-Ward, “Cemetery Design and Frederick Law Olmsted: Myth and Reality,” Sweet Auburn, Summer 1988.

Leave a Reply