Elegance and Beauty of Expression: The Early Stained-Glass Windows of Bigelow Chapel

Historical Collections January 3, 2023 Architecture

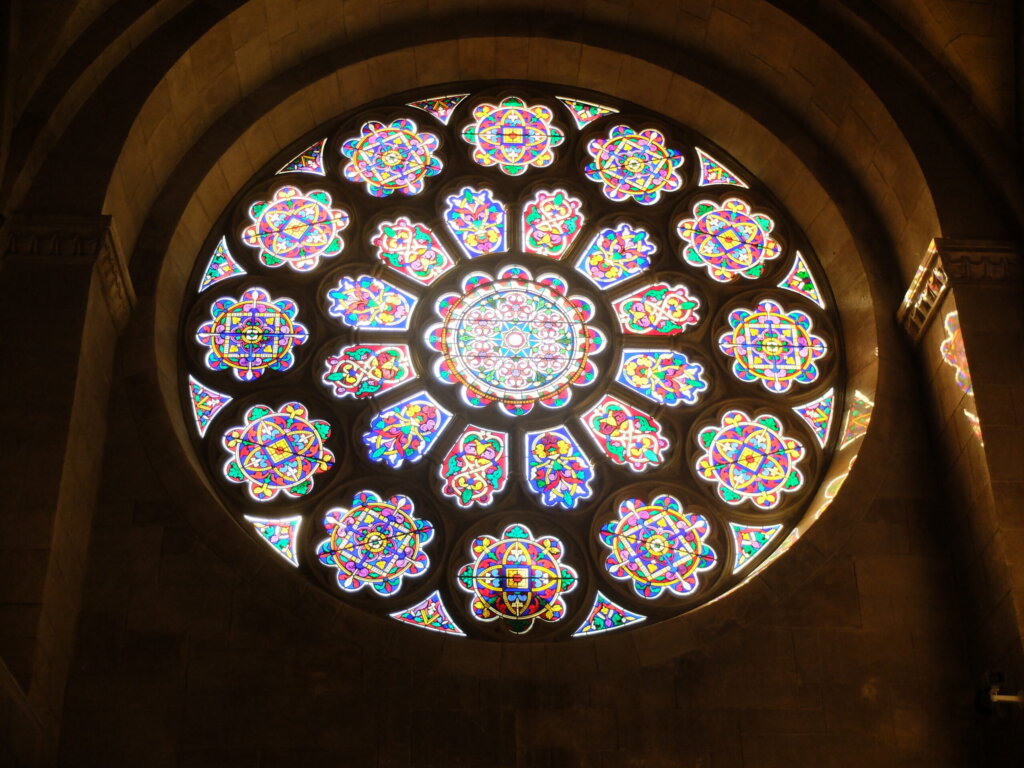

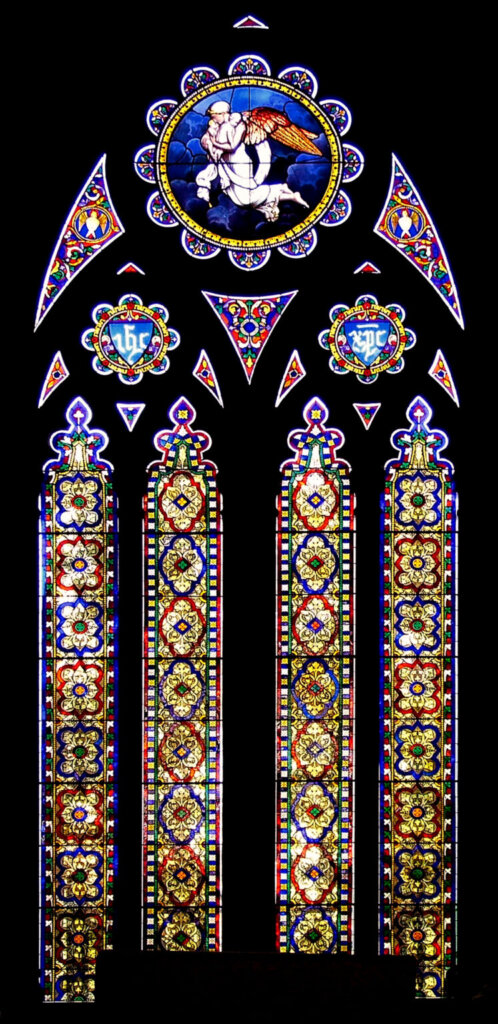

When entering Bigelow Chapel, one’s eye is immediately drawn to the brilliancy and beauty of its two large stained-glass windows: the Chancel Window, in the north wall of the building above the altar, and the Rose Window, in the south wall of the building above the entrance. “These two magnificent windows are part of Jacob Bigelow’s original conception for the chapel he designed in the 1840s,” Meg Winslow, Mount Auburn’s Curator of Historical Collections & Archives, observes. “The windows, like tapestries of shimmering light and color, unify the architectural space and bring a sense of nature into the building.”

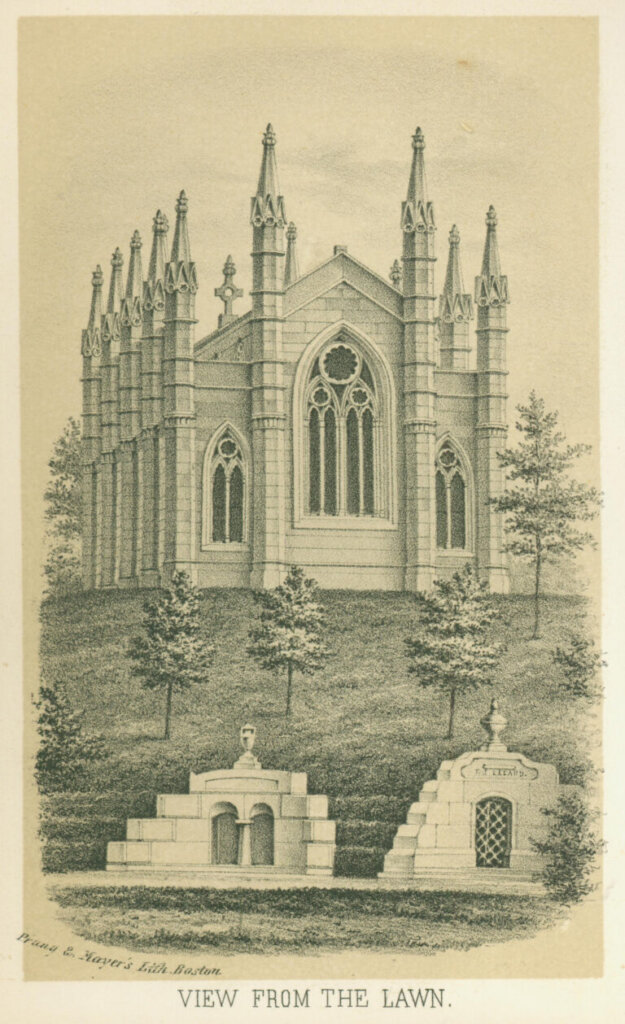

The Chancel and Rose Windows were installed in 1846, the same year the Chapel was completed.1 The first building at Mount Auburn, the Chapel was designed as a space for funeral and memorial services and to exhibit marble sculptures and works of art. Made of local Quincy granite with tall spires reaching toward the sky, the Gothic building fit well into the picturesque landscape as intended by the founders. Situated on the plateau of the first hill near the entrance, Bigelow Chapel continues to serve as a focal point for visitors today.

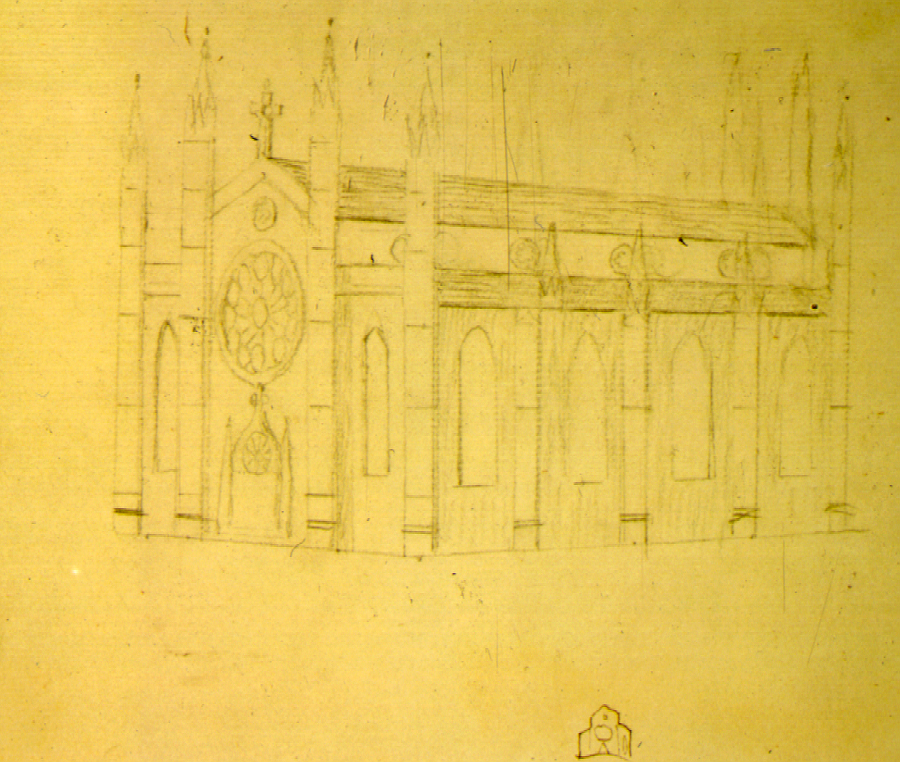

Dr. Jacob Bigelow, one of Mount Auburn’s founders and its second president, designed the Chapel with the assistance of the architect Gridley J. F. Bryant. A physician by training, Bigelow had an avid interest in architecture and published Elements of Technology, a book based on his lectures at Harvard on engineering, physics, and industrial design. For his design of the Chapel, Bigelow paid special attention to the stained glass, which he included in his first sketch for the building.

As few glass artists were working in the United States in the 1840s, Bigelow looked to Great Britain to commission the windows for his chapel. Scottish glass in this period was especially appreciated for its fine quality. In 1845, he mailed lithographic designs for two large windows to David Ramsay Hay, a prominent Edinburgh interior designer, known for decorating Holyrood Palace for Queen Victoria. Hay wrote back, recommending the Edinburgh firm of Ballantine & Allan: “These Gentlemen thus placed at the head of their profession, are intimate friends of mine and they are now engaged under my instructions in making the designs you require,” Hay wrote to Bigelow in 1845.2 “Their work in brilliancy and harmony of colour equals the best specimens of the antique, and far excells [sic] them in symmetrical proportion, as well as in accurate drawing.”3 James Ballantine and George Allan had recently been commissioned to create stained glass for the Houses of Parliament in 1844 (no longer extant). The following year, Ballantine published his book A Treatise on Painted Glass.

“We have studied carefully the best specimens of the Antique, in this country and on the Continent, and feel confident, that we can now produce windows, equally durable & brilliant, with the best of those specimens, and more in accordance with the principles of harmony in form and colour,” Ballantine & Allan wrote to Bigelow. “[We] should feel exceedingly delighted, to have the honour, and the advantage, through your means, of sending a specimen of our Art to your interesting country."4 Through this commission, Bigelow imported some of the finest artistry and latest techniques of the day exemplifying the revival of medieval colored and leaded glass windows. The Chancel and Rose Windows are significant early works by Ballantine & Allan and the first of their works to be shipped to the United States. As such, they represent some of the earliest examples of hand-painted stained glass of this kind and quality in the country.

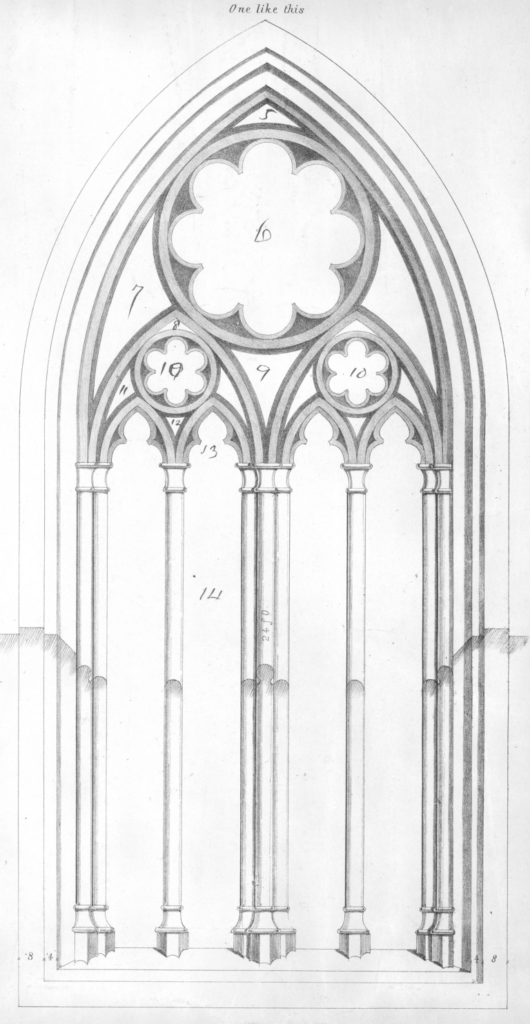

The long-distance correspondence between Bigelow and the firm necessitated clear instructions as to the exact design and installation of the stained glass and speaks to the skill of Ballantine & Allan as well as to Bigelow’s attention to detail. Ballantine explained, “Should you resolve upon employing us, it would ensure correctness if you would forward pasteboard or paper shapes, the exact daylight sizes of the various compartments. These templets or shapes must be numbered, and your lithograph drawings numbered to correspond.”5 Regarding the installation of the pieces at Mount Auburn carried out by local workers, Ballantine wrote, “The panels could be forwarded together with plans & written instructions, such as would enable any common Glazier to put them in―Especial care would be taken that the Glass was packed in a way to warrant its safety―Vessels leave Greenock every month for New York . . . and we could have the entire work finished within six or eight months from the time of its commencement.”6

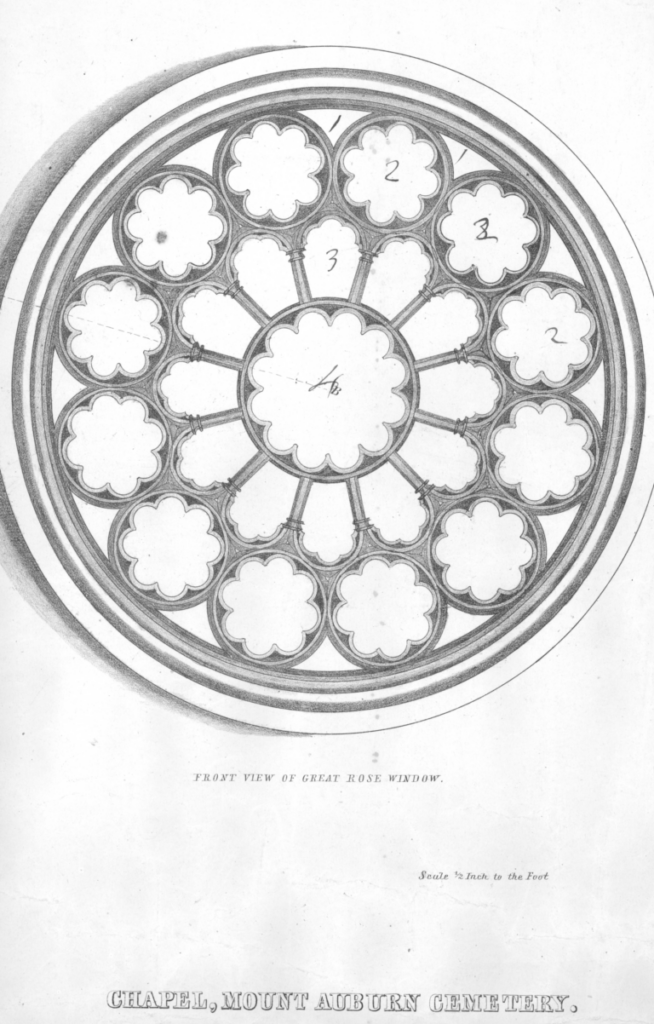

Ballantine & Allan practiced the mosaic style of stained glass that was comprised of many pieces of colored glass outlined, and held together, with lead strips called cames. The studio explained, “[O]ur Painted Glass is not executed in large Sheets, but like that of the Ancients is a species of Mosaic work―For example, the central compartment of the Rose Window, would be composed of upwards of one thousand separate pieces of Glass, the colour of which is in the body of the material, not merely fused on the surface―This mode produces the most brilliant effect, is much stronger than any other and when any repair is required small pieces are easily inserted.”7

For the center of the Rose Window, Bigelow originally chose the popular image of two cherubs, a detail from Raphael’s 16th-century oil painting Madonna di San Sisto, or the Sistine Madonna, one of Raphael’s most famous paintings, currently in the Dresden Museum. In 1852, this center panel was damaged in a storm and replaced with the ornamental floral panel we see today. The center circular window is surrounded by a circle of 12 petal-shaped windows. Around the petals another 12 circular panels form an outer circle, interspersed with 12 triangular pieces or kites. “The overall pattern is ornamental, in the revival style of the thirteenth century,” Winslow explains. “The design of the Rose Window is based on earlier medieval rose forms that are adaptations of Islamic patterns in imitation of nature. One of the most interesting details about the window is that it is framed in cast iron. Several cast-iron pieces are bolted together and then painted to match the appearance of stone, so the frame looks like stone but is in fact made of iron.” The window is 12 feet in diameter.

The Chancel Window measures 21 ½ feet high by 9 feet wide and includes 36 separate panels. Winslow learned from conservators at Serpentino Stained Glass Studio that it is comprised of approximately 4,200 individual pieces of hand-blown and hand-painted glass.8 A series of four lancets (tall narrow windows with arches) are surmounted by two smaller rose panels and above them, a larger rose figural panel. Triangular kite forms surround the three rose panels.

For the central panel, Bigelow asked that Ballantine & Allan’s initial recommendation of a religious scene of the Resurrection be changed to an image of the 1815 popular bas-relief Night and Her Children by the Danish sculptor Albert Thorvaldsen, a leader of the international Neo-classical movement. Bigelow, who owned a personal collection of bas reliefs and classical art, described Thorvaldsen’s popular image of an angel cradling two children as the “most beautiful and appropriate thing I have seen.”9 He advised the studio to use “cold and somber tints” as well as “bright & dazzling colors” and to “dispose the light & shadows in an artistic manner.”10 In Ballantine & Allan’s design, a winged female figure carries two sleeping infants in a deep blue background of billowing clouds. “This adaptation by the painter of Thorvaldsen’s relief carving into painted glass is extraordinary and contrasts with the surrounding hand-painted ornamental window designs,” Winslow says. “Here, the artist uses heavy enamel paints in a nineteenth-century style that is incredibly detailed. The rendering of the flesh and pink and white drapery textures is exquisite.”

A year after the Chapel’s completion, Cornelia Walter wrote in Mount Auburn Illustrated of the spiritual effect of light streaming through the stained glass. In a union of art and nature, the light with its “prismatic hues . . . reminds one by its radiance,” she wrote, of “the light and the darkness” and “mortality and immortality.”11 Today, the Chancel and Rose Windows, exemplifying as Ballantine observed, “an art remarkable for the elegance and beauty of its expression,” continue to inspire visitors to Bigelow Chapel as they did nearly two centuries ago.12

Citations

1 The Clerestory windows, along the sides of the building, were installed in the 1920s.

2 David Ramsay Hay to Jacob Bigelow, 28 Feb. 1845. Historical Collections & Archives, Mount Auburn Cemetery.

3 Hay to Bigelow, 28 Feb. 1845.

4 Ballantine & Allan to Jacob Bigelow, 21 Apr. 1845. Historical Collections & Archives, Mount Auburn Cemetery.

5 Ballantine & Allan to Bigelow, 21 Apr. 1845.

6 Ballantine & Allan to Bigelow, 21 Apr. 1845. The Chancel Window cost 100 pounds sterling, and the Rose Window cost 115 pounds sterling. Bigelow to Ballantine & Allan, 14 Jun. 1845.

7 Ballantine & Allan to Bigelow, 21 Apr. 1845.

8 Over the years, panels on the stained glass have suffered from glass deterioration and structural damage. Restoration and conservation specialists from the Serpentino Stained Glass Studio undertook extensive projects on the Chancel Window in 2006 and on the Rose Window in 2017.

9 Bigelow to Ballantine & Allan, 14 Jun. 1845.

10 Bigelow to Ballantine & Allan, 14 Jun. 1845.

11 Cornelia W. Walter, Mount Auburn Illustrated (New York: R. Martin, 1847), 37-38.

12 James Ballantine, A Treatise on Painted Glass Shewing its Applicability to Every Style of Architecture (Edinburgh: London, Chapman & Hall, 1845), 3.

Comments