Harriet Jacobs (1813 – 1897)

Toward the western end of Clethra Path is the gravesite of Harriet Jacobs, who is buried with her brother John Jacobs (1815 – 1873), and her daughter Louisa Jacobs (1833 – 1917). Raised in Edenton, North Carolina, Harriet and John Jacobs were born to Delilah Horniblow and Elijah Jacobs, a carpenter. Jacobs recalled a happy early childhood. “[We] lived together in a comfortable home; and though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed I was a piece of merchandise . . . .”[1]

After Delilah Horniblow’s death, Harriet and John went to live with Delilah’s enslaver Margaret Horniblow. Harriet was only six at the time. Though it was illegal to do so, Horniblow taught Harriet Jacobs how to read and write. “For this privilege, which so rarely falls to the lot of a slave, I bless [Margaret’s] memory,” Jacobs wrote.[2] Six years later, Harriet and John’s father, Elijah, died and was interred next to Delilah in a place known as Providence. Blacks in Edenton had purchased this tract of land communally and established a meetinghouse and graveyard there. For African Americans in the area, Providence represented “their crowning effort to create their own space,” scholar Jean Fagan Yellin writes in Harriet Jacobs: A Life.[3]

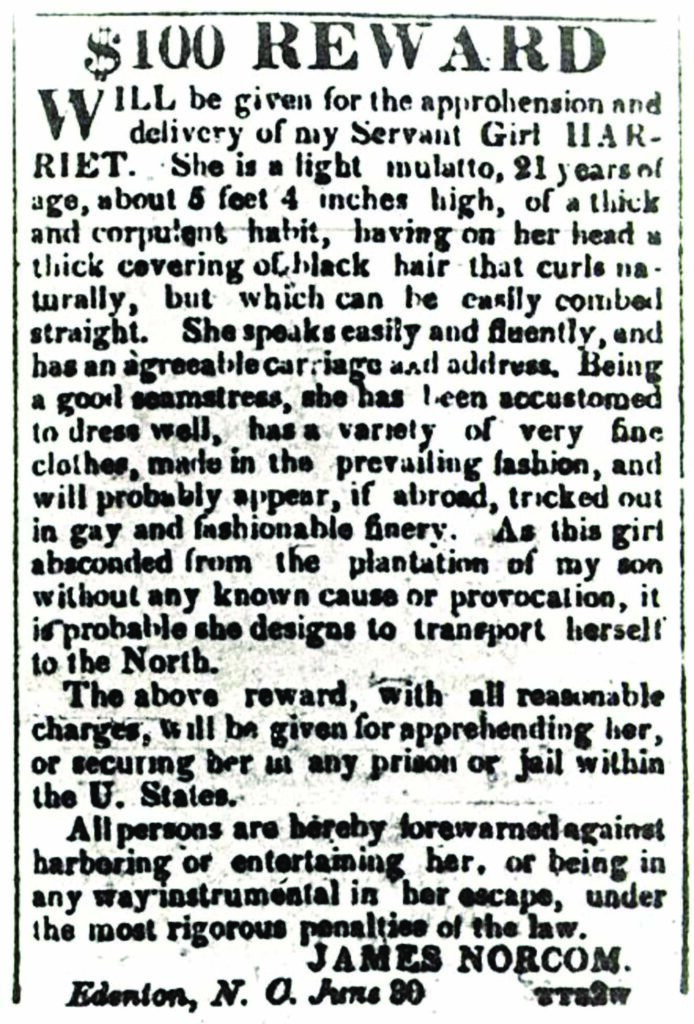

That same year Margaret Horniblow passed away, and the ownership of Harriet and John Jacobs was transferred to Horniblow’s three-year-old niece, Mary Matilda Norcom. But it was the child’s parents, Dr. James and Mary Norcom, who held ultimate power over the two siblings. Dr. Norcom was a wealthy owner of a large plantation, and in his household Harriet Jacobs met the harsh indignities of slavery as he began a relentless campaign of sexual harassment. “A sad epoch in the life of a slave girl,” Jacobs wrote. “My master began to whisper foul words in my ear. . . . I turned from him with disgust and hatred. But he was my master.”[4] Dr. Norcom denied Jacobs’s request to marry a free Black man. In an effort to ward off his advances, she started an affair with Samuel Tredwell Sawyer. A White man, Sawyer came from a family of colonial aristocracy, and practiced law in North Carolina. Jacobs gave birth to a son and daughter, Joseph and Louisa, by Sawyer. She hoped Norcom “would revenge himself” by selling her.[5]

Harriet Jacobs eventually escaped to the house of her grandmother, where she sought refuge for seven years. Cramped in a tiny crawlspace nine feet long and seven feet wide, unable to stand, Jacobs endured the stifling heat of the summer and the bitter cold of the winter. With the light from a small hole, she passed the time sewing, writing, and reading, gaining a self-taught education that would soon serve her well. Sawyer was eventually able to buy John, Louisa, and Joseph, and arranged for them to live with Harriet Jacobs’s grandmother. Only through the small hole could Harriet Jacobs gaze upon her beloved children.

When Sawyer later moved to Washington to serve in Congress, John Jacobs accompanied him and in 1838, during a family trip to New York City, he escaped north. In Rochester, New York, he worked in the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room and lectured widely throughout New York and Massachusetts. Sawyer arranged for Louisa Jacobs to live in Brooklyn, New York. In 1842, Harriet Jacobs’s family planned her own route north and, she was eventually reunited with her daughter. Later they moved to Boston where Joseph also joined the family. Harriet Jacobs finally felt “as if I was beyond the reach of the bloodhounds; and for the first time during many years, I had . . . my children together with me.”[6]

In 1849, Louisa Jacobs attended the Young Ladies Domestic Seminary School in Clinton, New York. That same year, Harriet Jacobs moved to Rochester where she became involved with abolitionists working at the North Star newspaper, operated by Frederick Douglass and located just above the Anti-Slavery Office and Reading Room that John Jacobs managed. In 1861, with the encouragement of the abolitionist Amy Post, she published a narrative Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl under the pseudonym Linda Brent. Many thought Lydia Maria Child, the book’s editor, was its author as they could not believe that someone born into slavery could write such articulate prose. Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl garnered a reputation as one of the most highly regarded autobiographical accounts of an enslaved woman in the antebellum South.

With the passage of the Fugitive Slave Law in 1850, John Jacobs decided to go to California and try his hand at gold mining. Joseph Jacobs accompanied him. They later traveled to Australia, where Joseph Jacobs settled—Harriet Jacobs would never see her son again. John Jacobs made his way to England where he found an audience sympathetic to his lectures about his life in slavery, and in 1861, he published a serialized narrative called A True Tale of Slavery, which had a wide following in London. On the eve of the Civil War he wrote to his sister from abroad, “I shall wait to see what course the North intends to pursue . . . . If [the American flag] must wave over the slave, with his chains and fetters clanking, let me breathe the free air of another land, and die a man and not a chattel.”[7]

After the Civil War, Harriet Jacobs returned to Cambridge, Massachusetts. “Although African Americans accounted for only twelve percent of the city’s residents,” Yellin explains, “Jacobs found Cambridge alive to the national struggle over the freed people’s rights.”[8] She opened a boarding house at 10 Trowbridge Street from 1870 to 1872, and residents included Harvard mathematician Chauncey Wright and then-presiding Dean of the Harvard Law School Christopher Columbus Langdell. In 1873, Jacobs operated another boarding house at 127 Mount Auburn Street. Mary Walker, who lived close by on Brattle Street, became a friend, and the two women, both from North Carolina, shared their experiences as mothers and fugitives from slavery.

John Jacobs eventually moved to Cambridge as well. Yellin writes, “For a brief few months, Harriet Jacobs lived a version of the life she had fantasized for decades: she was in her own home with her daughter, and her beloved brother and his boisterous children were close by. It was the achievement of a lifelong dream.”[9] Then John Jacobs died suddenly. William Lloyd Garrison praised Jacobs for asserting “his God-given right to be free,” and “in every situation leading an upright life, exhibiting a manly spirit, and commanding the respect of all who knew him.”[10]

John Jacobs’s remains were interred in Mount Auburn Cemetery in the family lot of James Burgwyn and his wife, Agnes Burgwyn, who was the daughter of Mary Walker, John Jacobs’s friend and neighbor. At that time, burial in a friend’s lot, if death was unexpected and no lot had been previously purchased, was not uncommon. Two years later in 1875, Louisa Jacobs bought a lot for her family on Clethra Path, where she arranged for her Uncle John’s remains to be reinterred. His burial place was in eyesight of Mary Walker’s grave.

Harriet and Louisa Jacobs then moved to Washington, D.C. Capitalizing on Harriet Jacobs’s fame as an author, the mother and daughter raised funds for food, clothing, and medical supplies for black soldiers and for those who had escaped from slavery into Union territory. They worked tirelessly to establish orphanages and schools for young African American children in Alexandria, Virginia, as well as in Edenton, North Carolina. As Harriet Jacobs’s health began to decline, Louisa Jacobs tended to her mother. She thanked Ednah Dow Cheney, a dear friend and an activist in the New England Women’s Club, for the money she had sent from herself and others to help her mother. She wrote to Cheney, “While it saddens me I am glad that friends think my Mother worthy of their sympathy. . . . Poor mother! I am afraid will never stand on her feet again.”[11] Harriet Jacobs died in 1897. “[She] was an heroic woman who lived in an heroic time,” Yellin writes. “Committing herself to freedom, she made her life representative of the struggle for liberation.”[12]

Although Harriet Jacobs had lived in New York City, Rochester, and Washington, D.C., Louisa Jacobs chose to bring her mother’s body back to Cambridge for burial in the family lot at Mount Auburn. The words she selected for her mother’s epitaph allude to Harriet Jacobs’s resilience and devotion: “Patient in tribulation, fervent in spirit in serving the Lord.” As Providence in Edenton represented a sacred burial ground for Harriet Jacobs’s family, so too did Mount Auburn. Their lot was located close to Mary Walker’s, and not far from many others they had known in Cambridge and Boston.

Upon her death in 1917, Louisa Jacobs was buried next to her mother and uncle. The family was reunited in a lot that today is often adorned with offerings—a flower, a rock, a note—left by visitors, who come to pay their respects. Years of exposure to the elements had weathered their memorials.

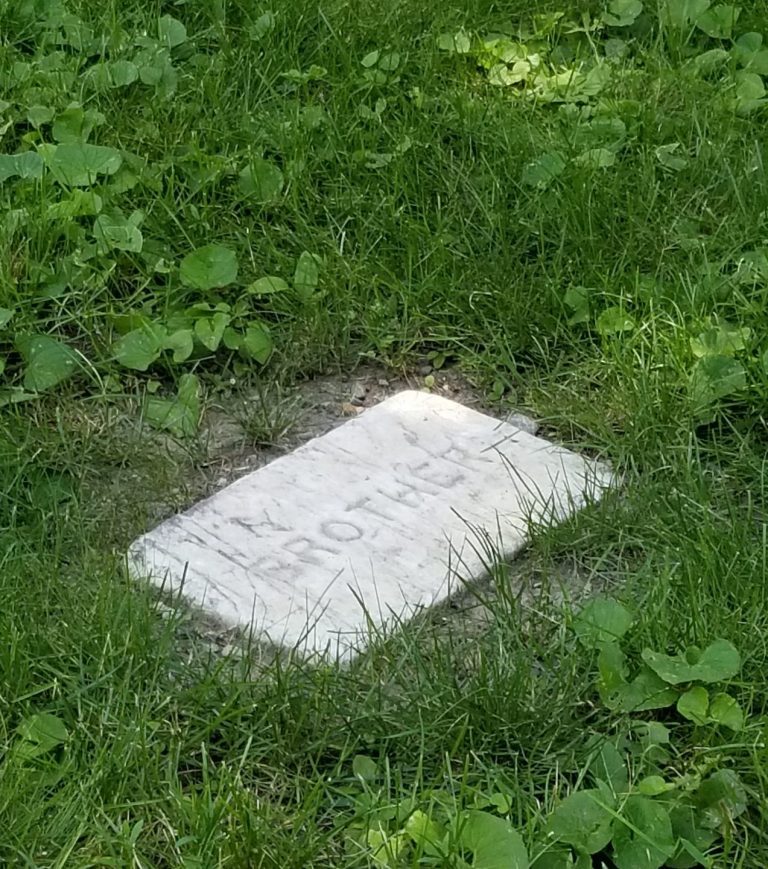

With support for the African American Heritage Trail, conservators washed the marble stones. Harriet Jacobs’s monument was re-set and re-pointed to stabilize one of the most visited memorials in Mount Auburn. Cemetery staff also located John Jacobs’s gravestone, which had sunk beneath the earth, so it could be re-set and viewed once again. By tapping into the ground they discovered the stone, a simple marker with the word “Brother.”

The Jacobs family is buried in Lot 4389 on Clethra Path.

Footnotes:

[1] Harriet Jacobs, Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988, pp. 11-12.

[2] Jacobs, Incidents, p. 16.

[3] Jean Fagan Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life. Cambridge, Perseus Books Group, 2004, p. 19.

[4] Jacobs, Incidents, p. 44.

[5] Jacobs, Incidents, p. 85.

[6] Jacobs, Incidents, p. 182.

[7] John S. Jacobs, “A Colored American in England.” National Anti-Slavery Standard, June 29, 1861.

[8] Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life, p. 219.

[9] Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life, p. 225.

[10] William Lloyd Garrison, In Memory, Angelina Grimké Weld. Boston: George H. Ellis, 1880, pp. 76-77 in Yellin, Harriet Jacobs, p. 226.

[11] Louisa M. Jacobs to Ednah Dow Cheney, July 22, 1896 in The Harriet Jacobs Family Papers: Volume 2. Ed. Jean Fagan Yellin. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 2008, p. 822.

[12] Yellin, Harriet Jacobs: A Life, p. 3.

Top Image:

Harriet Jacobs, 1894.