Time on the Horizon

Every August some friends and I gather for an annual “Nighthawk Watch” at the top of Washington Tower at Mount Auburn with legendary bird observer extraordinaire Bob Stymeist. While most of the attendees are skilled “birders,” I am more interested in just hanging back and loosely joining what always turns into an annual reverie on light – for the sunset, the cycles of life – a meditation on the horizon, as well as on the cusp of seasonal change set during the magic hour.

As I edge past half a century on this planet, I have begun to think that in addition to being on the neurodiversity spectrum, perhaps I am also crepuscular?

(more…)“A Most Beautiful and Commodious Building” Mount Auburn’s Story Chapel and Administration Building

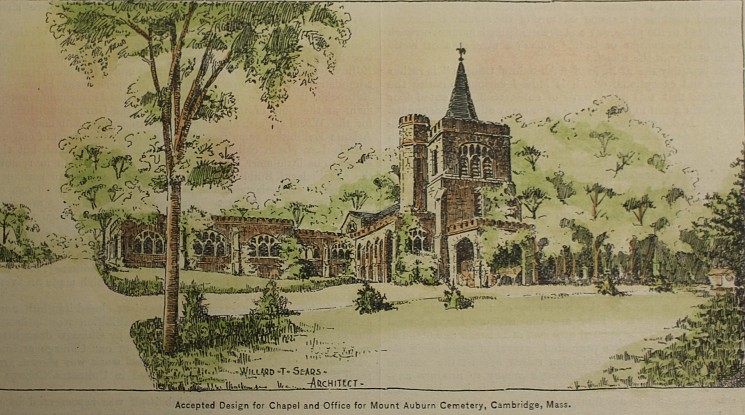

The first thing you see when you pass through the entry gateway of Mount Auburn Cemetery is Story Chapel and the adjoining Administration Building. Since 1898, the old stone building has provided a setting for funeral and memorial services; a meeting place for public programs and events; and offices where staff have carried out the work of cemetery services, and of preservation and cultural activities related to Mount Auburn. Masonry work, structural repairs, and major renovations on the interior and exterior of the building have been taking place since 2017. The multi-phased project gives us pause to reflect on the significance of the building in Mount Auburn’s history.

Decision to Build a New Chapel and Office

Construction on the original red sandstone structure started in 1896 and was completed in 1898, during a time when Mount Auburn was experiencing significant growth.[i] Bigelow Chapel, Mount Auburn’s first chapel erected in the 1840s and 1850s, had served the Cemetery for half a century. Increasing complaints about the building, however, included insufficient space for funeral services, no cellar or robing room, and poor heating. Bigelow Chapel’s challenging acoustics, as reported in a Mount Auburn Annual Report, became evident in the form of a “disagreeable echo, which interfered with the voice of the officiating minister and rendered choir singing impracticable.”[ii]

In 1895, a special committee appointed to investigate the renovation of Bigelow Chapel concluded that refurbishing the building would be equal to the cost of constructing a new structure.[iii] In addition, more space was needed for the Cemetery’s growing administrative staff. The committee recommended to the trustees the “construction of a new Chapel, and at the same time, and in connection therewith, a building for the offices of the Corporation. . . . By connecting the two buildings, both can be more conveniently and economically heated, and cared for.”[iv] The cost of construction totaled approximately $68,000.[v]

The trustees expressed their desire for a style of building in keeping with the other architectural landmarks within the Cemetery including the Egyptian Revival Gateway and Bigelow Chapel. A design competition included plans submitted by the architectural firms Longfellow, Alden and Harlow; Coolidge and Wright; G. Wilton Lewis; and Willard Thomas Sears.[vi] Sears, the chosen architect, designed the Old South Church in Boston’s Copley Square (1873), and was currently working with Isabella Stewart Gardner on Fenway Court, the home of Mrs. Gardner that later became the Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum (1900-1902). [vii] Sears would also oversee the interior renovation of Bigelow Chapel in 1899 for the installation of a new crematory.

New Chapel

Sears chose red sandstone quarried in Potsdam, New York for the construction of the Chapel and administrative offices.[viii] The stone was understood to be weather resistant and harder than granite, yet easy to carve. It was also known for its variegated colors that ranged from red to pink. Mount Auburn’s Annual Report noted that Potsdam sandstone “is a very hard stone and does not readily absorb moisture, and the color is very agreeable and pleasant to the eye. The buildings will be practically fireproof, built in the most durable manner.”[ix]

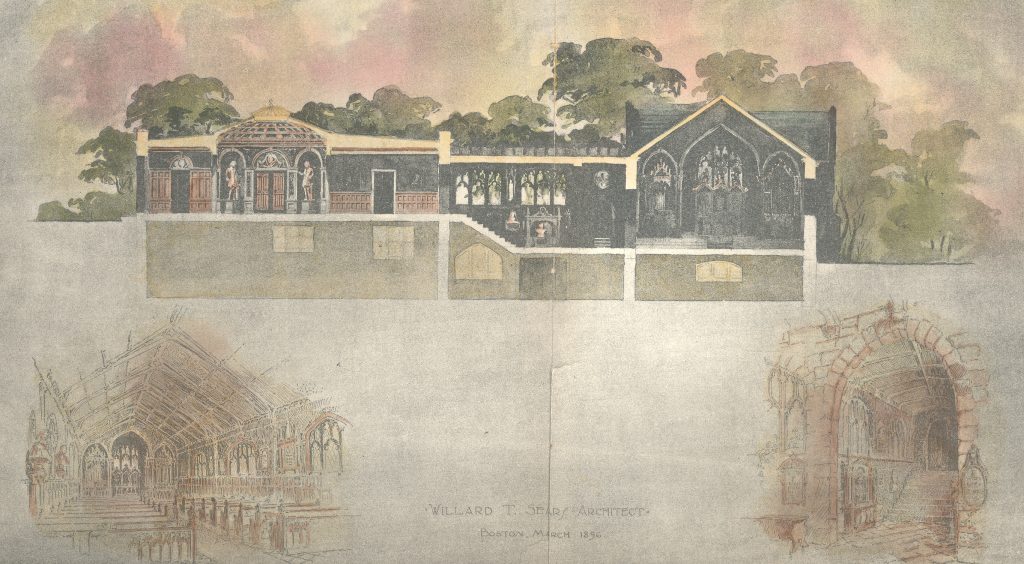

Israel Spelman, President of Mount Auburn during the time of the building’s construction, described Sears as “unremitting in his superintendence and personal attention.” [x] For the “New Chapel,” as the building was initially called, Sears explained, “The English perpendicular style of architecture as exemplified in many of the English parish churches built during the early part of the fifteenth century has been adopted.”[xi] The English gothic style was characterized by arches in the ceiling, large windows, and vertical lines in the paneling and window tracery (the support between sections of glass).

In the New Chapel, Sears placed Indiana limestone tracery along the windows and the interior wall between the nave (central part of the chapel) and the cloister (hall) running along the north side of the building. In 1929, the architectural firm Allen and Collens oversaw the installation of leaded and stained glass windows in the nave and the chancel (area near the altar). For the nave, the studio of Wilbur H. Burnham Sr. created gothic revival windows representing the medieval tradition that was favored by Burnham. The figures of Christ and angels are portrayed in the large chancel window above the altar and are signed by the Boston artist Earl E. Sanborn. While the symbolism is Christian, Sears designed the Chapel “to meet the requirements of all religious denominations.”[xii]

The interior walls were constructed with Pennsylvania golden bricks and laid in yellow mortar. The Chapel featured carved wooden hammer beams (horizontal supporting beams) with decorative angels, each holding a shield; carved wooden pulpits (elevated stands for speakers); and a total of 22 pews, 11 on each side of the aisle. All were made of Florida gulf cypress that reflect the Arts and Crafts aesthetic, and the woodwork was stained and rubbed down to achieve a flat oil finish. Together the pews and balcony, accessible by a stairway from the front vestibule, offered seating for 175 people, more than twice that of Bigelow Chapel. An organ chamber housed a Hutchings organ, which was replaced in 1925 with a Hook & Hastings model.[xiii] The vestry provided an office and changing room. A room near the Chapel entrance received caskets for funeral services. Unlike Bigelow, the New Chapel also had electricity.

Visitors entered the New Chapel on Central Avenue through a porte-cochere (covered porch). For the exterior, Sears designed a square three-story belfry (bell tower) with a turret and a spire (removed in 1935). Flat roof areas were covered with copper and the pitch roofs with slate. A sundial mounted on a tablet made from Indiana limestone was placed on the southern exterior of the building. Henry Ingersoll Bowditch acquired the bronze sundial from its previous owner Dr. Benjamin Waterhouse, a professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. The tablet is carved with ivy leaves, and clusters of engraved ornamental leaves surround the sundial. Bowditch’s son remembered that “My father . . . asked his friend, the poet John G. Whittier, for an appropriate verse to be engraved upon the [tablet].”[xiv]

The 1899 Annual Report observed, “The chapel . . . is furnished with every modern convenience and improvement, and the humblest as well as the most costly and expensive funeral services can there be satisfactorily performed.”[xv] The first funeral occurred on June 18, 1898, and 58 services took place in the first year. [xvi] In 1936, the New Chapel was named Story Chapel after Justice Joseph Story, one of the Cemetery’s founders and its first president.

In 1987, renovations in Story Chapel created improved space for lectures, events, and exhibits. The Visitors Center, located at the entrance to the Chapel, opened in 2008. In 2012, McGinley, Kalsow, & Associates built a new porte-cochere out of reclaimed southern yellow pine and created a more accessible and inviting entrance to the Chapel.[xvii]

Administration Building

The original design of Willard Sears included enclosed cloisters along the north wall and a passageway in the basement that connected the Chapel to the office (which became known as the Administration Building around 1900). There were staff offices on the first floor and basement as well as two fireproof storage vaults for safe storage of Cemetery records. The building provided a superintendent’s office, a meeting room for the trustees, and a business office for a bookkeeper and clerks.[xviii]

The office featured a center rotunda area that exhibited full-length marble statues of John Winthrop, John Adams, James Otis, and Joseph Story. The statues were moved from their previous location in Bigelow Chapel to be displayed in this new setting. In the 1930s, to create more office space, the trustees donated the four statues to Harvard University. [xix] In 1990, Ann Beha Associates renovated the interior in a way that modernized the office space and preserved the structure’s historic features. The skylight in the original rotunda used to display the statues, for example, was replaced with a lantern shaped light that brought natural light into the new offices.

A climate-controlled storage room was built on the lower level to preserve and increase longevity of the Cemetery’s historical collections and archives. In 2015, the family room and conference room where visitors first enter the Administration Building were redecorated. Today, Mount Auburn staff continue to carry out administrative, cultural, and preservation activities related to the Cemetery and to provide essential cemetery services.

When Story Chapel and the Administration Building were completed in 1898, the local press provided extensive coverage about the new structure. The Cambridge Chronicle wrote, “Externally, the chapel is replete with characteristic points of Gothic architecture. Window arches, buttresses, finials, roof effects, etc., are worked into a complete and harmonious structural scheme.”[xx] It described the structure as “a most beautiful and commodious building . . . . the only purely Gothic type of building this side of the Hudson [R]iver and the only one in New England.”[xxi]

While Story Chapel and the Administration Building have undergone changes over time, the historical integrity of the structure has been preserved. The current project, for example, includes restoration of the exterior stonework. Gus Fraser, Vice President of Preservation & Facilities, explains that “it was essential to select a replacement stone that would blend with the rich, reddish, earthy hues of the original Potsdam sandstone and complement the building’s characteristic glow in the afternoon light.” The multi-year project that began in 2017 ushers in a new chapter that continues a tradition of thoughtful renovations to preserve and enhance the historic building. Within its walls, staff dedicate themselves to the mission of the Cemetery and visitors continue to find solace and inspiration.

[i] Mount Auburn raised part of the funds designated for the cost of the new building by selling property it owned across from the Cemetery on Mount Auburn Street. Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 18, 1895, Special Meeting, 173.

[ii] Israel Spelman, Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 3.

[iii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 18, 1895, Special Meeting, 173.

[iv] Ibid.

[v] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[vi] Mount Auburn paid $100 to the architectural firms that submitted plans for the Chapel.

[vii] Willard Sears also designed the Pilgrim Monument in Provincetown (1907). Sears (1837 – 1920) is buried at Mount Auburn on Excelsior Path.

[viii] The Potsdam quarries, in use in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, supplied stone for buildings in New York State, New England, and Canada.

[ix] Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 4.

[x] Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1898, published 1899, 4.

[xi] Willard Sears, Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1896, published 1897, 4.

[xii] Ibid.

[xiii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, October 21, 1925. Minutes note that it was voted “that a new organ be bought from Hook & Hastings Organ Company for $7000, and allowance of $600 being made for the old organ making the net cost $6400.” Founders of the company, Elias Hook (1805-1881) and George Greenleaf Hook (1807-1880) are buried at Mount Auburn on Sorrel Path.

[xiv] Vincent Y. Bowditch, Life and Correspondence of Henry Ingersoll Bowditch, Vol. 1 (Boston: Houghton, Mifflin and Company, 1902), 239.

[xv]Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1898, published 1899, 4.

[xvi] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[xvii] The Cemetery removed the original porte-cochere at the Chapel entrance in 1971 as the stone was in poor condition and the entrance did not easily accommodate modern hearses and automobiles.

[xviii] Mount Auburn Cemetery Trustees Meeting Minutes, December 16, 1898.

[xix] The 1934 Annual Report noted, “It has been decided to give up the Boston office and consolidate the executive offices at Cambridge. . . . Not only will the consolidation result in a substantial saving in operating costs but it will eliminate duplications of work and promote greater efficiency of administration.” Annual Report of the Trustees of the Cemetery of Mount Auburn for 1834, published 1935, 4.

[xx] “New Mount Auburn Chapel,” Cambridge Chronicle, October 1, 1898.

[xxi] Cambridge Chronicle, September 3, 1898.

Carolina allspice, Sweetshrub

…But oh! For the woods, the flowers

Of Natural, sweet perfume,

The heartening, summer showers

And the smiling shrubs in bloom,…

-Claude McKay

English naturalist Mark Catesby (1683-1749) is credited with introducing Calycanthus floridus, Carolina allspice during his colonial explorations. His Natural History of Carolina, Florida and the Bahama Islands, was the first published work of the flora and fauna from these locations. Two large folio volumes with 220 personally engraved and individually hand-colored plates with descriptions were published between 1729 and 1747. In plate 46 he illustrated the Carolina allspice along with a cedar waxwing.

(more…)Songwriting for Mount Auburn – A Conversation with Todd Thibaud

In 2021, we made mini-grants to five artists to create original works inspired by the Cemetery during a one-year period. Each of the selected artists has created an original project rooted in their experiences at Mount Auburn. Today, meet singer-songwriter Todd Thibaud and learn about his creative process behind composing and recording two new songs related to Mount Auburn’s history.

Tell us a bit about yourself and your work.

I’m originally from Vermont, but moved to the Boson area in the late 1980s to be part of the incredible music scene that was happening around town. I was passionate about music and songwriting, but even so, at the time the idea of building a career as a musician felt elusive and dreamlike. Not long after settling into the area I started the band Courage Brothers with an old friend, Jim Wooster. We worked hard at writing, recording, and performing locally, and after a couple of years secured a record deal with a New England-based label called Eastern Front. That deal brought us national exposure and allowed us to get out on the road and tour the country. It didn’t take long for me to understand that I was hooked. I knew without a doubt that this was what I wanted to do with my life.

As often happens, our band eventually broke up, and I began my journey as a solo artist. It was a strange transition at first, but it was the right choice. I’ve always seen myself, first and foremost, as a songwriter. Everything else – recording, live performance, touring etc. – all stems from that. As an artist who tends to write from a personal perspective, being on my own has allowed me to let my songwriting go where it will, and to investigate the intricacies of life that inspire me most. I’ve been very fortunate to work for so long at something I love so much.

These days you can find me performing regionally, solo acoustic, with my band of talented musicians, or in duo/trio formats. I normally tour in Europe once or twice a year, but the pandemic has taken a toll on that part of my work. I’m looking forward to getting things back on track over there in 2023.

For your residency, you produced two original songs that both connect deeply with Mount Auburn’s history. Could you talk about the themes that these songs explore?

I think it’s easy and completely understandable to be swept away by the incredible beauty of Mount Auburn. That beauty certainly deserves to be acknowledged, but I also wanted the songs to be securely connected to Mount Auburn’s core mission as a place of rest for those who have passed on. In my writing process I never wanted to forget that for every stone there is a story: a life lived, whether short or long. And for the families left behind, the stone begins as a marker of grief, and only with time might it be seen as a place of comfort, healing, or inspiration.

I was also deeply inspired by the history of the place itself, the many remarkable people involved in its creation, and those laid to rest there. There are so many stories that deserve to be told. Initially, I felt pulled in several directions, but over time I settled on two distinct subjects. My goal then became to create two songs connected in different ways to our relationships with loss, grief, hope, and place. In addition, I wanted to keep both songs firmly rooted in the history and continued relevance of Mount Auburn Cemetery. My intent was to take a broader view in one song (Sweet Auburn), and a more personal, intimate approach in the other (Louisa May).

Tell us about your research process. What led you to pick these subjects for your songs?

One of the first things I read when I began my research was the text of Joseph Story’s Consecration Day address, given on September 24th, 1831. I was immediately drawn in by the beauty of the language and the powerful sentiment behind his words. It left me wanting to learn more about this remarkable man and this beautiful place he clearly loved so much. His address would remain a beacon for me as I continued my work over the next several months.

During my further research into Joseph Story, I learned that just five months before he would give his Consecration Day address, he had lost his beautiful young daughter Louisa May, age ten, to scarlet fever. I went on to discover that he had lost seven children previously, and that of his ten children only two survived to adulthood. I could only imagine the grief that this man must have carried. I couldn’t help but wonder what those months following Louisa May’s death must have been like for Joseph. And then, later that September when he stood in the Dell to give his beautiful address, what must he have been thinking and feeling in those moments? I knew that this was a story I wanted to tell.

At one point in my research, I stumbled upon a Boston area newspaper article written after Consecration Day, in 1831. The article explained that, in the late 18th century, prior to being known as Mount Auburn, the area had been affectionately referred to by visiting Harvard students as “Sweet Auburn.” The nickname coming from the poem, “The Deserted Village,” by Oliver Goldsmith. Almost immediately, I knew that one of the songs I would write would be entitled Sweet Auburn.

For songwriters, a good title can often provide a creative launching pad, allowing you to visualize a fledgling song as a completed whole. Not word for word, of course, but conceptually and directionally. I thought to myself, what if this beautiful place could tell us a bit of its own story? What would it want us to know? What would it say? This idea provided me with a clear framework to work within as I wrote my own version of Sweet Auburn.

Treating Mount Auburn as a living, breathing, sentient character allowed me to look at the landscape and its history in a more empathetic and personal way. Over the course of a few verses, I could treat the love and respect felt by so many for Mount Auburn as a two-way street. Doing so opened creative avenues that would have been harder to access had I taken a different tack. I’d never before taken this approach in my writing. I thoroughly enjoyed the process.

During your residency, you brought these songs from an initial creative concept into the final recording that audiences can listen to today. Could you talk about the steps that went into producing that finished work?

For these songs, the initial research process was a critical first step. Especially since my songs were primarily rooted in Mount Auburn’s history. I wanted to gain some understanding of the time, and a sense of what was important to the founders and citizens of that era. It was important to me to not simply tell stories steeped in historic fact, but to connect these songs to the deeper emotional energy behind these events. It’s easy sometimes to view historical figures in a one-dimensional manner. But behind each well-known name of history, there was a living, breathing human being, as vulnerable to the pains, tragedies, and challenges of the human experience as you or I. I wanted to make sure that the songs acknowledged those deeper layers.

The next step was the writing itself. What always works best for me is to make extensive handwritten notes. To write down everything that strikes me as important, and to let that information percolate in my thoughts for a period of time. I like the physical notebook because I can leaf through it whenever I want, circle passages that hold special weight, and write side notes or quick lyric snippets that might eventually work their way into the song. I’ll often have a melody idea in my head as I’m working on lyrics, which can help with the phrasing and cadence of each line. Once I have a key phrase, or a few verse lines to work with, I’ll work with my guitar to refine the form and the melody. That refined form provides me with a template to work within as I make progress toward the finished lyrics. It’s often a process of trial and error. Writing and re-writing. Moving lines, changing single words. My goal is to settle on what feels most true and honest, and to discover what approach conveys the essence of the song most effectively. If I feel moved by a passage, my hope is that the audience will as well.

Throughout the songwriting process, I’m already thinking ahead to how I’d like to record the tracks. Songs tend to have a “voice” about them, and if you’ll let them, they’ll often guide you to where they should land. In the case of these songs, I knew that I wanted to keep the production very intimate and traditional. I wanted them to sound as much “of the time” as they could. To help achieve that, I reached out to a longtime collaborator of mine, Sean Staples. Sean is an extremely talented multi-instrumentalist, who is very knowledgeable about traditional music arrangement. He was invaluable in the final production of these songs.

I had been thinking that it would be nice to connect the recordings to Mount Auburn in some way, and wondered if we might be able to set up in Bigelow Chapel and record the songs there. Everyone at Mount Auburn was very accommodating, and Sean and I spent a day there in early April recording in the incredible acoustics of that space. We later took those performances to Sean’s personal studio so that we could add some additional instrumentation before declaring the songs complete. From that point it was up to me to create the final mix of each song, and then arrange for them to be mastered by a mastering engineer. That final stage gives you the finished versions that you can hear now.

How has your connection to Mount Auburn evolved during your residency?

I love the place! I’m smiling as I say that, but it’s true. I’ve really developed a deep love for Mount Auburn, and a personal connection to the place and its people that fills me with gratitude. Inspiration is everything for a songwriter, and Mount Auburn has inspired me on so many levels. It’s been an honor and privilege to tell some of its story. And if these songs might somehow come to occupy a small sliver of space in Mount Auburn’s ongoing history, it would be deeply gratifying to me. I feel tethered to the place now, and it’s now become an important part of my own personal story.